Premis:

Politicians request architects to design governmental buildings on the basis of a national story or vision, with the intention to make the building, in the future, shape the practices and mentality of new generations.

Abstract

As long as politically administrative units have existed, there have been buildings to house official functions. Over time, these buildings have increasingly been commissioned to symbolise a national culture or identify a national story. Modern research into the development of symbolism in government architecture has largely been isolated to post-colonial states, showing how those governments use architecture to tell a story of national independence. This dissertation aims at investigating a similar relationship between governments, nations and their buildings. The goal is to examine the premise that architects design governmental buildings based on a national story or vision, to make the building, in the future, shape the practices and mentality of new generations.

This dissertation will examine the early modern governmental architecture of both countries in the Nineteenth Century, the post-war era of government expansion and the decades surrounding the move to the Twenty-first Century. To do that, we will apply a theoretical approach other writers have used when studying post-colonial states to cases found in Norway and England. It will be argued that politicians in the Nineteenth Century commissioned buildings that had clear, direct visual links to classical architecture, while the post-war era exhibits a wish to rewrite the national story following international modernism’s focus on liberating architecture from national considerations.

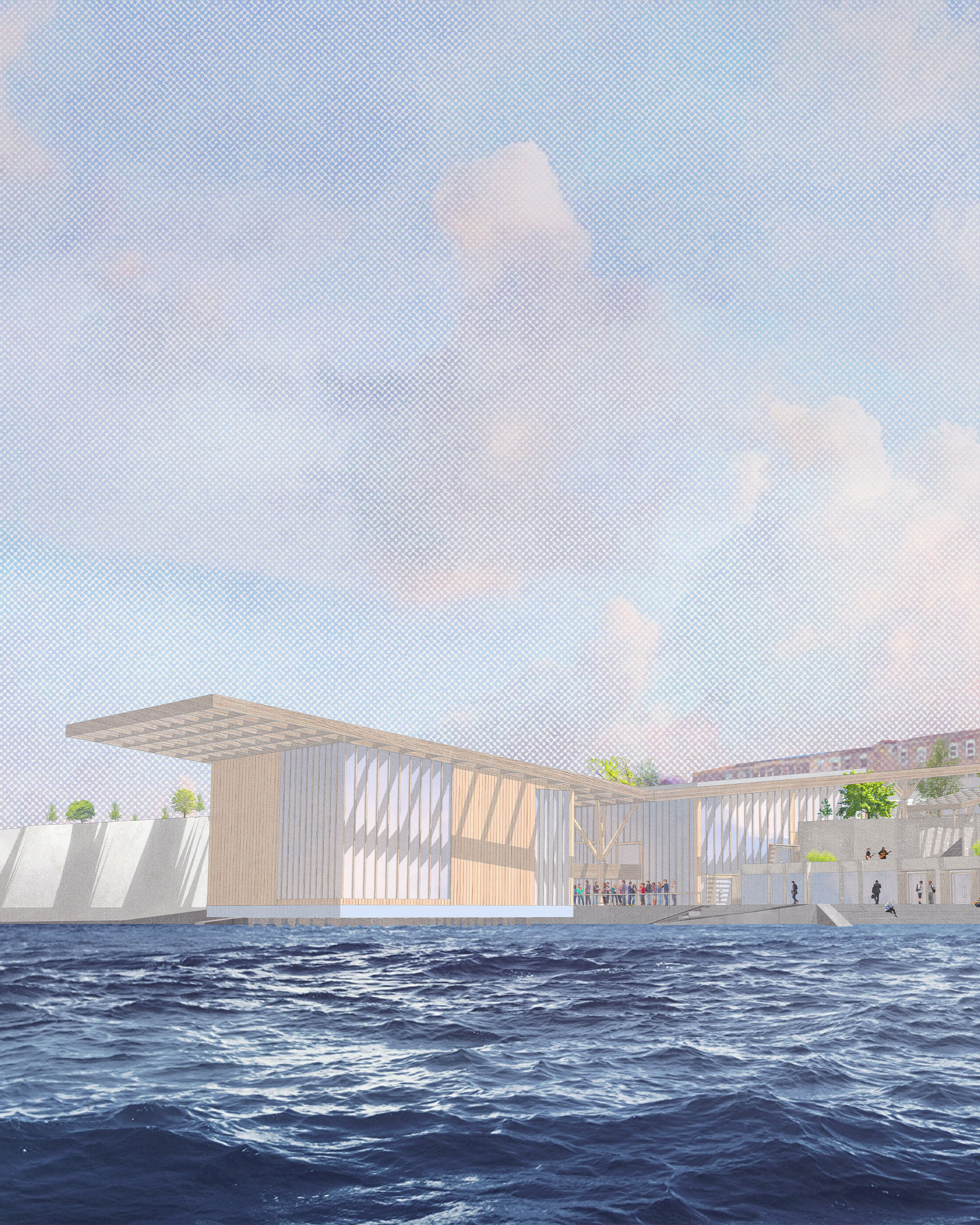

Contemporary government architecture from 1992 until today contrasts this by following the lines of critical regionalism where physical references to the nation’s history are used to write a progressive story of democracy and openness. Because these two countries were so different in wealth and power, we will be able to identify the founding logic behind government architecture transcending nationalities and economic wealth. By comparing and contrasting examples across 200 years, we see that governments always use architecture to draw a curated image of the national culture and memory so that the buildings in the future can inflict the designed mindset onto new observers and users. ●

We shape our buildings; thereafter our buildings shape us.

Winston Churchill

Top image: The circular court of the Treasury building, Government Offices Great George Street by John Brydon (1898), photographed by me.